Margin debt is shrinking — so will the bull market morph into a bear?

CHAPEL HILL, N.C.—A surprise drop last month in margin debt — what investors have borrowed to buy stocks –doesn’t signal the end of the bull market.

A bear market could begin at any time, of course, but if one does, it will be for other reasons.

FINRA last week reported that total margin debt contracted 4.3% in July, the first monthly decline in 15 months. While some are viewing this drop as the harbinger of a new bear market, the historical data doesn’t support their concern.

That’s because margin debt is not a leading indicator of the stock market. It doesn’t give us any insight into the market’s trend that we couldn’t already get by simply focusing on a chart of the S&P 500 SPX,

Margin debt instead is a coincident indicator, rising when stocks go up and falling when the market declines. I documented this by analyzing the relationship since 1970 between margin debt’s trailing 12-month rate of change and that of the dividend- and inflation-adjusted S&P 500. The r-squared of this correlation is an impressive 47%. That means that the S&P 500’s gyrations explain 47% of contemporaneous changes in margin debt.

But I came up empty when using margin debt’s 12-month rate of change to forecast the S&P 500’s return over the subsequent 12 months. In this case there was no statistically significant correlation. The same was true when I used margin debt’s one-month rate of change to forecast the S&P 500’s subsequent returns.

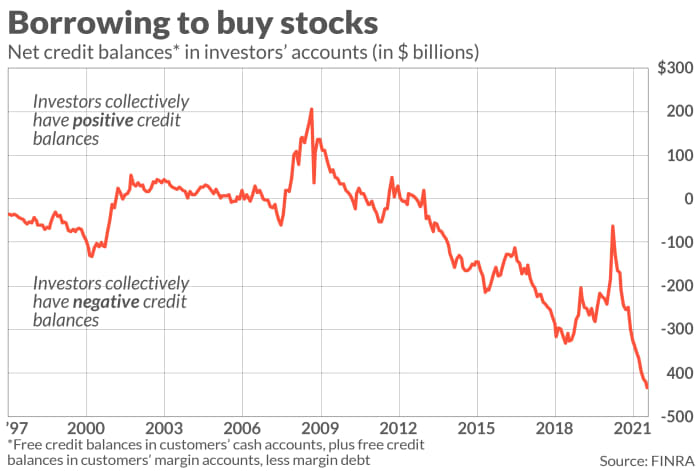

There is another reason not to read too much into margin debt’s drop in July: When margin debt is netted out with free credit balances in investors’ cash and margin accounts, the July numbers are entirely unexceptional.

I got the insight to focus on this net number from Lance Roberts, chief investment strategist at RIA Advisors, and the accompanying chart plots it. As you can see, investors on balance have been going further and further into debt for many years now. July’s total, which is the right-most data point on the chart, is simply a continuation of the trend.

In an interview, Roberts argued that margin debt, either by itself or when netted against investors’ free credit balances, isn’t in and of itself a problem. It only becomes one during market declines, when it can make the decline much worse. It increases market risk, in other words. But the spark that ignites that decline will be something else besides margin, he says.

I also have a more cynical reason to question the bears’ argument that margin’s decline in July heralds a new bear market: This spring, when margin debt had been rising for many months in a row, some were arguing that the ever-rising margin debt was bearish. They were wrong, of course, for all the reasons discussed here. But if the bears are being consistent, they can’t argue that both rising and falling margin are each bearish.

In fact, however, the trends in margin debt are neither bullish nor bearish. So if you want to worry, find something besides margin debt to worry about.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.

Plus: ‘Something will give’ in U.S. stock market amid ‘discomforting sentiment signals,’ Citi warns