Why the U.S. dollar continues to rise, defying a 2021 consensus trade

The U.S. dollar didn’t get the memo.

A weaker U.S. dollar, courtesy of trillions of dollars in fiscal stimulus, a dovish Federal Reserve committed to letting the economy and inflation run hot, rising public debt and twin government budget and international trade deficits, was the consensus call coming into 2021.

Instead, the U.S. currency has appreciated versus major rivals as the first quarter comes to a close, with the euro EURUSD,

The dollar’s unexpected resilience has implications for other assets. A weaker dollar was seen as a boon for U.S. equities and, even more so, for international stocks. A weaker dollar was also expected to help provide a lift for emerging markets. It was also expected to provide a tailwind for booming commodities.

So why is the dollar rising instead? At the top of the list, analysts said, was Europe’s struggles with rolling out COVID-19 vaccines. A rise in infections and new and extended business lockdowns in several European countries are weighing on economic growth expectations for the eurozone, translating into weakness for the formerly robust euro.

“The dramatic divergence of European and U.S. growth expectations is a legacy of poor management on this side of the Atlantic and will leave scars in market pricing,” said Kit Juckes, a London-based macro strategist with Société Générale, in a note.

“Consensus forecasts look for 2021 eurozone GDP growth to be 1.5% slower than in the U.S., a relative deterioration of 3% since last September and 2.2% since the end of 2020. That gap needs to stop widening, at the very least, before it’s safe to sell the dollar again,” Juckes wrote.

Meanwhile, a robust U.S. economic performance could mean divergence in monetary policy, with the Fed set to begin tightening monetary policy relatively more quickly than the European Central Bank. That could see the pace of dollar appreciation accelerate this year, wrote analysts John Shin, Ben Randol and Athanasios Vamvakidis of BofA Global Research, in a Tuesday note.

A sharp pullback by global stocks and other assets viewed as risky would likely add to dollar strength, given the currency’s traditional role as a haven during periods of financial market volatility, the analysts said.

“Buoyant global risk appetite, rising expectations for global recovery and Fed complacency pose the greatest risks to our constructive USD view,” they said. “The Fed has been much more effective in its communication than the ECB, keeping the USD down despite a much worse eurozone economic outlook.”

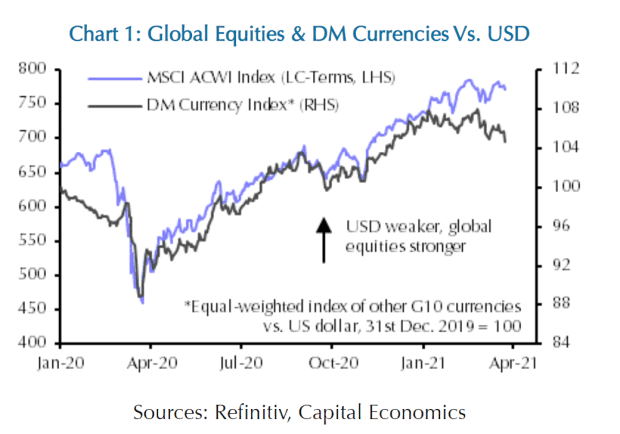

Meanwhile, the dollar’s relationship with global equites and other developed market currencies has changed, said Oliver Allen, markets economist at Capital Economics, in a note.

For much of the pandemic, there was a relatively strong relationship, with a weaker dollar translating into stronger global equities (see chart above). That occurred as central banks across the developed world cut policy interest rates to what they considered the effective lower bound and pledged to keep them there for some time, which meant relative moves in interest-rate expectations were fairly small, Allen explained. As a result, investor appetite for risk, which tended to mean a weaker dollar, became the main driver of developed market exchange rates.

The relationship started to break down at the beginning of this year, however, as the dollar took back some ground even as global stock markets continued to climb, Allen noted. While risk appetite has probably continued to influence developed-market currencies, it’s been overwhelmed by the surge in U.S. bond yields, which have been sharper than elsewhere, he said.

Capital Economics expects the dollar to strengthen against the yen and euro because bond yields in Japan and the eurozone have the least scope to rise.

“Policy makers there appear less willing to accept higher long-term yields and, in the case of the eurozone especially, we think that economic recoveries could underwhelm,” Allen said.